What we believe can make us more or less receptive to God

Sermon by Andy Wurm, Sixth Sunday of Easter, 17th May, 2020

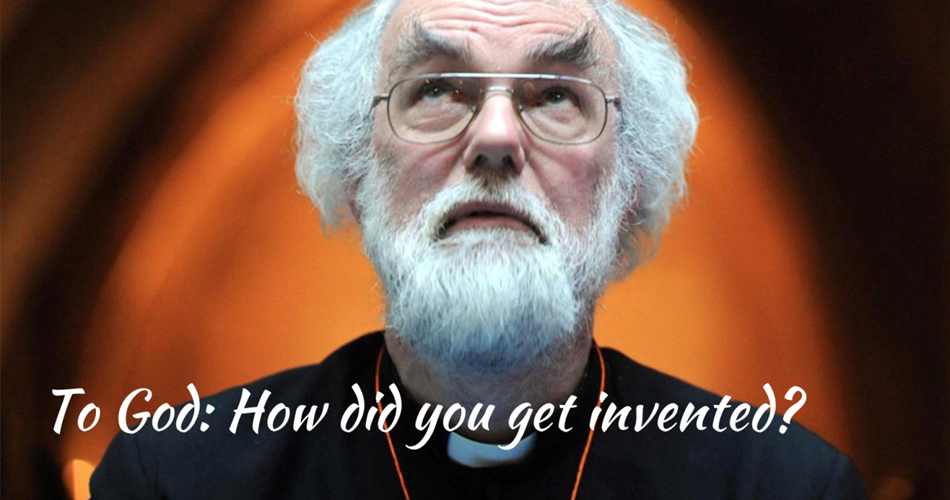

Some years ago, a six year old girl named Lulu wrote a letter to God and asked her parents to post it. Being atheists, they struggled to know how to respond. In the end, they sent it to the Archbishop of Canterbury, at that time being Rowan Williams.

Lulu’s letter went like this: ‘To God, how did you get invented? From Lulu xo’.

This was the Archbishop’s reply: Dear Lulu, your dad has sent on your letter and asked if I have any answers. It’s a difficult one! But I think God might reply a bit like this –

‘Dear Lulu – Nobody invented me – but lots of people discovered me and were quite surprised. They discovered me when they looked round at the world and thought it was really beautiful or really mysterious and wondered where it came from. They discovered me when they were very very quiet on their own and felt a sort of peace and love they hadn’t expected.

Then they invented ideas about me – some of them sensible and some of them not very sensible. From time to time I sent them some hints – specially in the life of Jesus – to help them get closer to what I’m really like. But there was nothing and nobody around before me to invent me. Rather like somebody who writes a story in a book, I started making up the story of the world and eventually invented human beings like you who could ask me awkward questions!’ And then he’d send you lots of love and sign off. I know he doesn’t usually write letters, so I have to do the best I can on his behalf. Lots of love from me too. +Archbishop Rowan

Lulu’s father said he was touched by this more than he would have imagined. His scepticism about religion and his cynicism about the Anglican Church, didn’t dissolve, but he said that these things were quite easily put to the side in the face of the Archbishop’s kindness and wisdom. He had won his respect. As for Lulu, the letter went down well. She particularly liked the idea of ‘God’s story’. Although she said she had very different ideas, she thought the archbishop’s ideas were good.

A good thing about others asking about God, is that it’s a chance to clarify what God is for us. That was the case for St. Paul, upon finding an altar to an unknown God in Athens (Acts 17:22ff). Paul begins his response by noting how ‘extremely religious’ the people of Athens were, thus respecting their openness to more than they already understood or accepted, although his comment that they were ‘extremely religious’ can also mean ‘superstitious’. Such intentional ambiguity would be appropriate in regard to our society too, where religion is very much alive and well, yet much of it is of questionable value. I’m not just talking about organised religion, but all that functions in a religious manner, such as sport, nationalism, and worship of the self, for example. Paul uses the opportunity of the altar to an unknown god to introduce his beliefs about God to the people of Athens, and we are given the condensed version of his speech. Paul may have been simply trying to win people to his cause, but probably not, for there is much more at stake in sharing religious beliefs, e.g. in those days Christianity offered a way of deliverance from at least some forms of oppression. Beliefs can change lives.

There are situations in which it is appropriate for Christians to challenge existing beliefs or practices, but perhaps the most important contribution of Christian belief to our society is the simple sharing of ideas for people to consider. In this way people don’t ‘get’ converted, but may convert themselves (not necessarily to following Jesus, but converted to the same values he held). That doesn’t necessarily mean arriving at particular beliefs, but hopefully becoming more human.

The example of Lulu and the archbishop is a good one, where neither she nor her parents finished up believing what the archbishop believed, but did change their beliefs or their attitudes in response to his. And he no doubt, was affected by Lulu’s invitation. This is why often when we read scripture, the best outcome may be not what answers or further insights we get, but what questions are raised for us. Rather than being filled with more information, our minds and hearts are stretched.

When it comes to believing in God, there isn’t really one view, even within Christianity, so it’s pointless asking exactly what it is that Christians believe. In the bible, even within a single psalm, there can be contradictory statements about God. For this reason, Christianity isn’t so much a set of beliefs about God, as a set of rules to guide our formulation of beliefs about God. The church is therefore the community of people who use those rules. Like a game of footy, even though everyone plays by the same rules, it doesn’t mean their experience will be the same.

Beliefs are not the most important thing though. What matters most is how we act (for ourselves and also in relation to others) as well as how we connect with God, however, as six year old Lulu knew, what we actually believe still matters. If we are going to pray, for example, we need a God we are comfortable praying to. So, what rules help us believe in a God we are comfortable with? And by comfortable, I include room for a degree of discomfort, in the same way that a relationship with someone you love includes being challenged to become more.

When it comes to rules for shaping beliefs, the number one rule for me is the notion that here is only one God. The importance of that is that if there’s only one God, then there are no other gods, which means God has no competition. If that’s the case, then has God has no opponents which threaten, so God is therefore not against anything or anyone, either needing to remove them or defend against them. In short, God does not engage in rivalry. That means God’s love is for all. God is not on anyone’s side more than anyone else’s, although people may put themselves offside with God by engaging in rivalry themselves. If God does not engage in rivalry, then our value and the meaning of our lives are set, and we have no need to compete with others or pursue approval from others. We are free to be what God created us to be and free of our need for everything and everyone to be as we want. There is nothing we can do to make ourselves loved more by God, so we are free of guilt and shame for our shortfalls and also free to make mistakes as we explore how to be human with each other.

God’s unconditional love both exposes how we are caught up in rivalry and sets us free from it. If we are truly open to what that means, we must accept that we share in the human condition with every other person, and so in regard to our standing before God and our worth as individuals, we are no better than others, and those we judge worse than ourselves are not judged in that way by God. For that reason, by engaging in rivalry with them through our judgement, we close ourselves off from God’s love and the freedom it empowers us with. By judging others, we make judgement the source of our value and meaning. And in so doing, have moved away from belief in one God to idolatry.

Giving up our engagement in rivalry and allowing ourselves to be set free from its grip on us, does not mean that what we do and what others do doesn’t matter. We still have to find ways of responding to abuse and oppression that lessens harm and requires responsibility be taken, but that is different to judging the worth of ourselves and others, and the meaning of our lives.