The resurrection occurs ‘out there’ and within us

Sermon by Andy Wurm, Easter 21st April 2019

All biblical experiences of resurrection (meeting the risen Christ) involve people with some sort of prior connection to Jesus. Doesn’t that make the accounts of people who claim to witness the resurrection suspect? Of course they would say he rose from death. They have a vested interest in that. But to think like that is to fail to grasp that the resurrection involves the coming to life of Jesus and those close to him. There is one person in the Bible who met the risen Christ, without having met him before, and that was St Paul, but he was closely tied to Jesus through persecuting his followers. This tells us something about how the resurrection can transform us too. It also explains why, although forgiveness of sins, (i.e. being set free from our compulsion to sacrifice one another) is given to us as a gift from God, repentance is necessary to receive it, so that it can transform our lives. Please notice though, this is the opposite of being forgiven only if we repent. God does not forgive us because we repent. We repent because we have been forgiven.

There’s a television series called Anh Do’s Brush With Fame. It’s a series in which the Vietnamese comedian interviews people, while painting their portrait. I really enjoyed the episode where he interviewed singer Jessica Mauboy. Jessica Mauboy has an extremely warm and bright personality. She is so down-to-earth and straight-forward, and has a clear sense of what has shaped her life to make her the person she is today. When Anh Do asked about the influence of the runner Cathy Freeman in her life, she spoke about the day Cathy Freeman visited her school and inspired her to become what she is today. Just the memory of that visit made her more animated, until Anh Do suggested there were dozens of little girls who in twenty years’ time will say that Jessica Mauboy came to their school and changed their lives. Initially, she reacted with joy, but as she began to describe how happy that makes her feel, she began to cry, because I think she was overwhelmed with the awareness that she was talking about having received something wonderful that was bigger than herself and wanting to pass it on. She was like Mary Magdalene meeting the risen Christ at the tomb, realising that what had happened to him, had happened to her as well, and she wanted to share it with others – described in the gospel as telling others she had ‘seen the Lord’

It was only possible for Jessica Mauboy to give to others what had been given to herself, because she had received it through repentance. Only if we understand this, can we know what resurrection is.

Jessica Mauboy said that what touched her about Cathy Freeman’s visit to her school was that she was an indigenous girl, who shared her culture, had been through many of the same struggles in life, but showed her that there was light at the end of the tunnel. Cathy Freeman showed her that it doesn’t matter what your background is – the important thing is what’s inside and what can be generated, so that what you can give is more important than your past. Anh Do noticed that she said what she could GIVE, rather than what she could ACHIEVE, and she responded saying that she loves being on stage and without a thought about anything else, is able to just to give the gift that is purely herself. Jessica Mauboy may not be able to live that way all the time, but what she describes in that interview is a textbook account of being shaped by the resurrection of Christ.

I mentioned before that biblical characters who encounter the risen Christ had a specific connection to Jesus, which allows us to see what’s going on, but for people who aren’t in the Bible, the same life transformation can happen with or without that. What that interview showed, was that Cathy Freeman’s influence enabled Jessica Mauboy to realise the possibility of disengaging herself from what she refers to as ‘her past’. By that, she means that which defined what she was and what she could be. She had been awakened to the possibility that she could let go of that and be free of any restrictive influence it had on her. That is freedom from rivalry, from the mechanism of violence, which gave her a restricted sense of what she could be. Repentance, in her case, involved letting go, giving up, what had previously defined her, and thus releasing within herself a new potential – not the ability to achieve things (which means playing the games involved in having to be a somebody, who is special and stands out from others), but a potential which allows her to be herself and give herself to others. The world can never take that away from her, because it didn’t give it to her.

Now I want to share a different experience of resurrection, in which a person is able to break free from the power of rivalry, be true to themselves and give graciously, even within an institution which persecutes them. James Alison is a Catholic theologian, who happens to be gay. Some years ago, he was told that unless he was sacked, certain religious superiors would no longer support the college he taught at. It was a devastating blow. His gut reaction was to respond by playing the victim card. That would involve adopting one of the mechanisms of violence our culture gives us, which is the sacred victim: a role he could have used as a weapon to attack one of the stereotypical ‘baddies’ which our culture also gives us – namely, in this case, judgemental and oppressive religious leaders. But, he says, God had other ideas, and while on retreat, he learnt a greater truth about himself, which set him free.

His first discovery was becoming aware that God had nothing to do with the oppression he was experiencing. It was simply a mechanism of human violence, of rivalry, and nothing more. He came to this awareness, when he realised that only a few of his critics had actually ever met him, so their attack could not be taken personally. They were just caught up in a mechanism of violence so much, that they couldn’t see it. When he realised he was dealing with a mechanism, whose participants were its prisoners, he could begin to forgive them.

Further than that, he also came to see how, in fact, he too, had bought into the mechanism of violence, as he had been on a crusade of sorts, powered by a deep resentment towards individuals and an institution which had persecuted him. He had been trying to manipulate the church into accepting him, because deep down, he did not believe God accepted him. He had sought a sense of self from the church, instead of God. But the church is a human structure, and like any human structure, it is incapable of providing a true sense of self to us. Only God can do that. He had been trying to acquire an acceptable identity within structures which are shaped by and create rivalry, and the only way you can do that, in the midst of such violent structures, is through violence. He describes that course of action as a form of idolatry – worshipping the church, not God. (God is the only One who can give us our true identity, for God is free of violence and rivalry, and so unconditionally loving.) On becoming aware of this, he realised that he too was in need of forgiveness. It was through repenting of, or letting go of, his own participation in the mechanisms of violence, that allowed him to receive forgiveness.

This is the forgiveness, or setting free, from mechanisms of violence that the risen Christ provides for us, shown to us in the gospel account of Jesus forgiving those who killed him. It is in appropriating this forgiveness for ourselves that allows us to also forgive others, and then be truly free to give ourselves to others, as Jessica Mauboy put it. Or, in the language of St Paul, writing to the Christians at Colossae, it’s the process of setting your minds on things that are above, not on the things that are on the earth, for

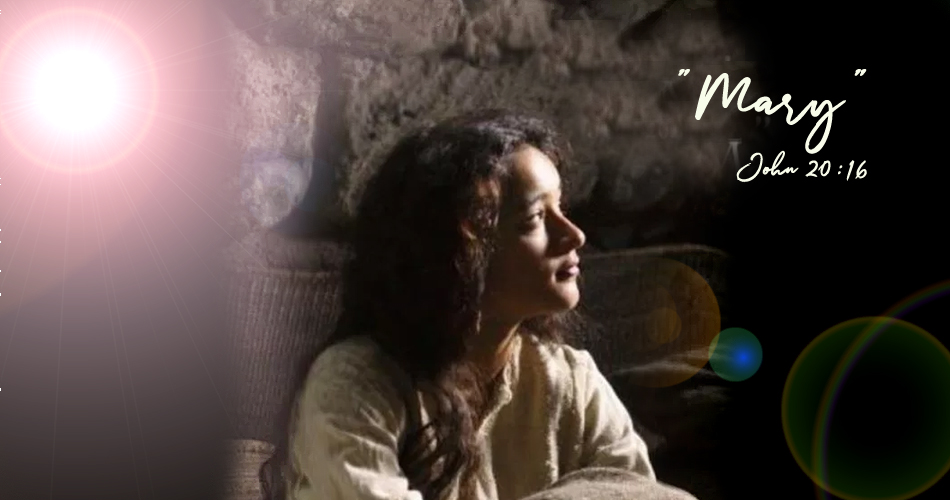

you (as defined by mechanisms of violence) have died and your life is hidden with Christ in God. In other words, your true identity is given by God. And we see that played out by Jesus asking Mary the rhetorical question – whom are you looking for? She says she is looking for him, which is the opening he is waiting for, where he can provide who she is really looking for, which is herself. He then gives her her name: her true identity: Mary.