Sunday Services are currently on hold due to Covid-19.

Tag Archives: featured

EASTER SUNDAY SERVICES

There will be Easter Sunday Services online from both Crafers and Bridgewater

CRAFERS

Led by Andy Wurm from Crafers Church:

Easter Day 11.30am

Streaming on the Parish Facebook page – https://www.facebook.com/stirlinganglican

BRIDGEWATER

Led by Barbara Messner

Easter Day 9.30am (but connection available from 9.20am)

Interactive via Zoom.

The link is: https://us04web.zoom.us/j/8357002111?pwd=UlFpOHZJQzhsT0gxdHllQ3dKTENSQT09

On Easter Day, please bring with you

1. A candle and matches, or a torch, or some other light to make shine (as our candle lighting at the beginning);

2. Bread and wine or some other food and drink, maybe chocolate or some other celebratory morsel (for an ‘agape’ meal in place of the Eucharist); and

3. Something that represents new life for you personally e.g. an object, picture, brief incident or recollection, something you can show or talk about very briefly (about 30 seconds to give space to all) as our shared reflection.

Do what’s comfortable to you – you are of course still welcome without any of the above.

Good Friday Zoom from Bridgewater 9.30am

Led by Barbara Messner from “Cyber- Bridgewater”:

Good Friday and Easter Day 9.30am (but connection available from 9.20am)

Interactive via Zoom.

The link for both days is:

https://us04web.zoom.us/j/8357002111?pwd=UlFpOHZJQzhsT0gxdHllQ3dKTENSQT09

Good Friday Service on Facebook

GOOD FRIDAY SERVICE

Led by Andy Wurm from Crafers Church:

Good Friday at 11.30am

Streaming on the Parish Facebook page – https://www.facebook.com/stirlinganglican

This will be a service of prayer, sermon and music by Seb, Alex and others.

PDF’s of hymns below:

Drop Drop Slow Tears The Royal Banners When I Survey The Wondrous Cross

Holy Week News

“Zoom” into Church

Barbara Messner is inviting you to three scheduled Zoom meetings for worship.

This Sunday will be a trial run with no communion, but with discussion.

These are Bridgewater worship style with PowerPoint but others are welcome.

On Easter Sunday, use your own bread and wine for virtual communion.

- Palm Sunday Zoom Meeting

Time: Apr 5, 2020 09:15 AM Adelaide - Good Friday Zoom Meeting

Time: Apr 10, 2020 09:20 AM Adelaide - Easter Sunday Zoom Meeting

Time: Apr 12, 2020 09:20 PM Adelaide

The link is the same each time:

Join Zoom Meeting ( <- click link)

If you are asked to enter a PASSWORD use : 899929

Meeting ID: 835 700 2111

How to Meditate

HOW TO MEDITATE

Sit down. Sit still and upright. Close your eyes lightly. Sit relaxed but alert. Silently, interiorly begin to say a single word. We recommend the prayer-phrase, ‘Maranatha’. Recite it as 4 syllables of equal length. Listen to it as you say it, gently but continuously. Do not think or imagine anything (and have no expectations). If thoughts and images come, these are distractions at the time of meditation, so keep (gently) returning to simply saying the word.

World Community for Christian Meditation – South Australia

There is no death in God

There is no death in God

Sermon by Andy Wurm, Lent 5, 29th March 2020

For today’s sermon, I’m going to walk through the gospel passage for today – John 11:1-45, commenting as I go.

Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha. Mary was the one who anointed the Lord with perfume and wiped his feet with her hair; her brother Lazarus was ill.

It’s interesting that we haven’t got to the part of John’s Gospel which tells of Mary anointing Jesus with perfume, yet he refers to it as having happened. This shows how the gospels are not meant to be read as historical documents, in the sense of this happened and then that. It also shows how often something only makes sense in the light of what comes later, and this is definitely so with this entire story. In mentioning Mary’s anointing of Jesus, the gospel writer alludes to what Mary was doing in that anointing. In one way, it was pointing to what was to come: Jesus’ death, but on another level, it was a response to Jesus as the presence of God, who is constantly flowing out of him/herself as generous love. Mary mirrors what she sees in Jesus. Only after the resurrection will she realise that she can do more than mirror that. She can be a source of generous love too, and in fact, that is actually the point of her life. That is what Jesus alludes to when he later tells his disciples (and John passes on to us!) that they will do greater works than he did.

So the sisters sent a message to Jesus, “Lord, he whom you love is ill.” But when Jesus heard it, he said, “This illness does not lead to death; rather it is for God’s glory, so that the Son of God may be glorified through it.”

The word ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘fame’, which would mean this is happening to make God more famous, rather ‘glory’ means reputation. To see the glory of God then, is to see what God is really like. In other words, this event, of Lazarus’ death, will show what God is like.

Accordingly, though Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus, after having heard that Lazarus was ill, he stayed two days longer in the place where he was. Then after this he said to the disciples, “Let us go to Judea again.”

It’s odd to say that even though Jesus loved Martha, Mary and Lazarus, he didn’t bother to go and see them when they needed him. That’s because there’s a mistranslation. The gospel writer doesn’t say though Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus, but because Jesus loved them. The translators couldn’t bring themselves to say that Jesus intentionally didn’t go to see them, because they can’t see why he would do that. After all, he’s so caring, and isn’t this story about how much he cared? Well, it is, but his caring is far deeper than for Lazarus and his sisters. If this event is to show us what God is like, then Jesus must wait for Lazarus to die before he goes to him. This is not a random act. Jesus never does random. All his actions have a purpose.

The disciples said to him, “Rabbi, the Jews were just now trying to stone you, and are you going there again?” Jesus answered, “Are there not twelve hours of daylight? Those who walk during the day do not stumble, because they see the light of this world. But those who walk at night stumble, because the light is not in them.”

In John’s Gospel, Jesus isn’t tempted by the devil in the wilderness. This is John’s temptation scene. The disciples tempt Jesus to avoid danger and thus give up on his mission. Rejecting their suggestion reinforces his sense of purpose. Later, the phrase ‘come and see’, usually used for others to come and see Jesus, reinforces the fact that he is discerning his purpose. Now is the time for him to act.

After saying this, he told them, “Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I am going there to awaken him.” The

disciples said to him, “Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will be all right.” Jesus, however, had been speaking about his

death, but they thought that he was referring merely to sleep. Then Jesus told them plainly, “Lazarus is dead. For your sake I am glad I was not there, so that you may believe. But let us go to him.” Thomas, who was called the Twin, said to his fellow disciples, “Let us also go, that we may die with him.”

Jesus explains that Lazarus really is dead. Whatever he does for Lazarus shows what God does with death, and will encourage belief in him. This will not be a miracle though. It is not even to be an amazing event. Later in the gospel, Lazarus is mentioned amongst guests at a party. No-one even bats an eyelid that someone who died is alive again. That’s because this is not about Lazarus, but what God does with death.

When Jesus arrived, he found that Lazarus had already been in the tomb four days. Now Bethany was near Jerusalem, some two miles away, and many of the Jews had come to Martha and Mary to console them about their brother. When Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went and met him, while Mary stayed at home. Martha said to Jesus, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.

Martha is not happy with Jesus. She redirects her grief onto him, blaming him for her brother’s death. How often does grief become the funnel for other emotions? Sometimes people allow loss and grief to define who they are and what they do – like Captain Ahab and the great white whale.

But even now, (Martha goes on,) I know that God will give you whatever you ask of him.” Jesus said to her, “Your brother will rise again.” Martha said to him, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.” Jesus said to her, “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him, “Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.”

Whatever the resurrection and the life is, it is not just a future thing. Jesus emphasises “I AM the resurrection and the life”, meaning I am that for you now. The same is true for us, Jesus can raise us to new life, here and now.

When (Martha) had said this, she went back and called her sister Mary, and told her privately, “The Teacher is here and is calling for you.” Martha doesn’t understand what Jesus is talking about, so she pretends he wants to talk to her sister.

And when (Mary) heard it, she got up quickly and went to him. Now Jesus had not yet come to the village, but was still at the place where Martha had met him. The Jews who were with her in the house, consoling her, saw Mary get up quickly and go out. They followed her because they thought that she was going to the tomb to weep there. When Mary came where Jesus was and saw him, she knelt at his feet and said to him, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.”

Mary repeats what Martha says to Jesus, but in a different tone. Kneeling at his feet, as one who learns from a teacher, indicates she is open to the possibility of there being more going on than she realises.

When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. Jesus said, “Where have you laid him?” They said to him, “Lord, come and see.” Jesus began to weep. So the Jews said, “See how he loved him!”

This is the key line in the whole story. It seems that Jesus is showing empathy for those he loved and then expressing his love for Lazarus, but that’s not the case. There is something far more profound going on here. We’re told that Jesus cried, while everyone else was weeping. Two different Greek words are used here. They’re not the same thing. The weeping of Mary, Martha and everyone

else, is ritual wailing, which would have been led by professional mourners. There would have been

some grief being expressed, but it was much more than that. That’s what Jesus was crying over. And he was also crying because he knew that what was going on in that ritual response to a death, would lead to his being killed. The job of professional mourners was to stir up grief. Especially in a case where someone was killed by the Romans. They would stir up feelings, encouraging hatred, emphasising enmity. It’s a practice that still works today. In 1989 Slobodan Milosevic got his Serbian people all riled up by digging up the casket of a 600 year old Serbian commander who had been killed in battle by their ethnic neighbours. That drove them to a war of ethnic cleansing, in which they killed thousands of people. It makes me wonder what our nation is doing with Anzac Day commemorations. Is there more going on than just honouring those who died, or reminding ourselves of the cost of war? And why did we spend 170 times as much commemorating World War One, as the French did, even though they lost 28 times more soldiers than we did? The bible tells us that death is an intrinsic part of human (fallen) culture. The rivalry that leads to it and the rivalry it creates forms and strengthens our sense of who we are. You might say ‘but as Christians, don’t we make an individual’s death define who we are?’ The Crusaders definitely did that. They rallied soldiers to the cause around the fact that the Muslims had taken control of the holy sepulchre (the supposed grave of Jesus). But they overlooked the fact that the grave was empty, which completely reverses the possibility of using death and sacrifice to justify being against others. It undoes all that.

We are told that Jesus was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved, but that’s a mistranslation. What it says in the Greek is that he snorted angrily and shuddered. That is the divine response to human culture which is so bound to death.

I have mentioned a few examples of being bound to death in order live. Also what comes to mind is how much death features in so many of the stories of our culture – in books films, television and games. Death is a key part of them. We might think they are just stories, but there is only so much death in our stories because it is culturally significant. One reason Jesus died is to undo our holding on to death and undo our fear of death. He could only do that by dying and then coming back to life. That makes sense for our fear of biological death, but this is not only about that. It is also to do with killing and sacrifice involving being against one another, being jealous, being threatened, being in rivalry. By raising Lazarus to life, Jesus is showing us God is profoundly NOT involved in death. That includes all that is oppressive and life-denying. It’s when we use religion, or laws, or anything else in our culture, to deny life, rather than help it flourish. This story tells us that death, which we think is integral to our lives, does not have to be. I have highlighted some of the ways we allow that to be, but there is much more, for example, what does it mean for biological death to mean nothing to God? The answer to that, and realising that life without the rivalry that leads to death and which creates death, is possible, is what radically changed the lives of the early Christians. It was the way they began to live completely unthreatened by others and be able to forgive and love them, that the writer of John’s Gospel refers to as ‘believing in Jesus’.

It was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. Jesus said, “Take away the stone.” Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, “Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead four days.” Jesus said to her, “Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?” So they took away the stone. And Jesus looked upward and said, “Father, I thank you for having heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.” When he had said this, he cried with a loud voice, “Lazarus, come out!” The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go.” Many of the Jews therefore, who had come with Mary and had seen what Jesus did, believed in him.

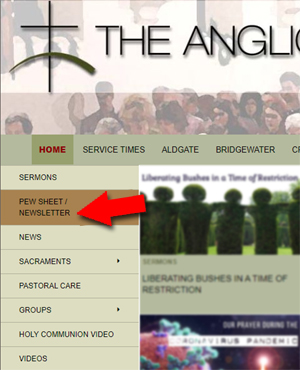

Newsletter to Replace Pew Sheet

Instead of the weekly Pew Sheet we are currently producing a weekly newsletter.

The weekly newsletter will appear on the Pew Sheet page which you can access by clicking HERE or use the Pew Sheet / Newsletter menu button at the top of the left column on any page.

This Newsletter is to temporarily replace the weekly Pewsheet, so please contribute when you can by contacting Katrina at Parish Office. Thank you!

Liberating Bushes in a Time of Restriction

Yesterday I liberated our woolly bushes from the temporary fence which has stood behind them while they grew to hedge height. Today I pruned them so that they wouldn’t droop under their own weight of undisciplined growth.

Both actions symbolized for me some inner longing.

Acting on that impulse gave me a sense of hope and meaning in this time of coronavirus restrictions and losses.

I had gone to sit on the deck behind the woolly bushes and their fence, where I tried to pray and meditate. After dissolving in tears for all that we are missing in our religious and communal life at present, I had this sudden urge to take away the fence that separated me from the woolly bushes.

What did that action represent? I guess I was feeling restricted, like the woolly bushes trying to poke through the gaps in the stiff ugly temporary fence and growing distorted in the process. Mind you, when I took away the fence, the branches fell about in all directions, hence the pruning of the next day. Now the growth is slightly reduced but shaped to come together in a more connected, upstanding and graceful way.

Is that what will happen for us and our churches in this time of restriction? The Archbishop sounded a similar note in an email letter to clergy, in which he urged us not to combat anxiety or to justify our existence by making ourselves overly busy. Instead he suggested that we might be refreshed and inspired if we find time to read, reflect, and pray. In other words, prune back the excesses and encourage centred growth.

The encouragement to take time for spiritual disciplines and refreshment applies to us all. Maybe people in the wider society might feel the need for spiritual meaning and refreshment themselves. In part, my urge to liberate the woolly bushes expressed a desire to be more in touch with the beauties of the created world which refresh and inspire me.

Although we can’t meet for worship on the last Sundays in Lent, or, more devastating still, for Holy Week and Easter Sunday, perhaps we are being guided to enter more deeply into the spiritual disciplines of Lent, to share in the passion of Christ played out in our world, and to wait eagerly for new life to emerge from an empty tomb. There are signs already of how the restrictions placed upon humanity may mean revival in the created world: pollution lifting over Italy with few people using vehicles, and dolphins and fish returning to the canals of Venice. Maybe liberating woolly bushes is symbolic of increased world-wide awareness of the need for revival of creation by the restriction of the rampant overgrowth of human exploitation of natural resources for profit. Suddenly we are also made uncomfortably aware of how quickly shortages can occur when people are greedy and don’t think of others.

So what has liberating woolly bushes got to do with Jesus raising Lazarus, or the prophet Ezekiel calling on the dry bones to connect and stand up, ready for the breath of the Spirit? Both those stories are about liberation from death, loss and grief, and coming forth into renewed life empowered by the Spirit of God. When I saw that these were our stories for this Sunday, I was moved by how powerful they were to offer hope in this pandemic.

Reading how Jesus shouted loudly to Lazarus: “Lazarus, come out!”, I longed for Jesus to shout: “People of God, come out!”

We were already shut away by those who think we are a dying breed. The instruction to “Unbind him and let him go!” seems even more poignant, as we feel ourselves to be bound and hampered without our communal life. How changed was Lazarus by his experience? Who might we become if our time of loss shapes and disciplines us? Mind you, there was no easy road ahead for the revived friend of Jesus.

When the story spread, and more people believed, the chief priests and the Pharisees plotted to kill not only Jesus, but Lazarus as well. We don’t know the outcome of that for Lazarus. How would you feel having been restored from death to find yourself threatened with death again soon after? Such could well be the case for humanity if those in authority refuse to admit the need for change.

The story of Lazarus began with Jesus delaying his departure to go to his friends in their time of need until after Lazarus is dead. Both Martha and Mary reproached him with this delay, saying: “Lord if you had been here, my brother would not have died.” Sometimes we feel that God is absent in the worst of times, or that God fails to act to save us from anxiety and sorrow. Yet the suffering we experience prompts us to call on God with great intensity as the psalmist does in the first verse of Psalm 130: “Out of the depths have I called to you, O Lord: Lord, hear my voice.” There is something powerful and necessary in waiting for God that makes us more aware of how important God is to us. Verses 5 and 6 evoke that intense longing for God that causes us to look for the coming of a new day:

“I wait for the Lord, my soul waits for him: and in his word is my hope. My soul looks for the Lord more than watchmen for the morning, more, I say, than watchmen for the morning.”

Let me share with you some quotes from Brian McLaren’s book Naked Spirituality. Those of you who received Richard Rohr’s emails this week will recognize what McLaren says:

“When we call out for help, we are bound more powerfully to God through our needs and weakness, our unfulfilled hopes and dreams, and our anxieties and problems than we ever could have been through our joys, successes, and strengths alone. . . .”

Later McLaren writes:

“Along with our anxieties and hurts, we also bring our disappointments to God. If anxieties focus on what might happen, and hurts focus on what has happened, disappointments focus on what has not happened. Again, as the saying goes, revealing your feeling is the beginning of healing, so simply acknowledging or naming our disappointment to God is an important move. This is especially important because many of us, if we don’t bring our disappointment to God, will blame our disappointment on God, thus alienating ourselves from our best hope of comfort and strength. . .”

Returning to the story of Lazarus, I find another insight related to what McLaren says about naming our pain: it’s necessary to grieve, to share in the general pain of loss even if we do hope for restoration.

Some of the most moving verses in Scripture are verses 32 -36 of John 11: “When Jesus saw her weeping and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. He said, “Where have you laid him?” They said to him, “Lord, come and see.” Jesus began to weep. So the Jews said, “See how he loved him.” It’s necessary to see, and to weep. That’s an expression of love.

I struggle with the call to see and to weep. I want to avoid seeing and I don’t want to weep, afraid of being overwhelmed. But Ezekiel could not channel the Spirit to raise the dry bones until he was transported to the valley, and until he was led around and saw how many and how dry the bones of the people of Israel were. The Spirit says: “Mortal, can these bones live?” and the prophet answers, “O Lord God, you know.”

Many churchgoers must be asking “Can these empty churches live?” Our humble answer must be, “O Lord God, you know.” Then we may be given words to speak or write, invoking the renewal of form and life.

Perhaps like the liberated and pruned woolly bushes, new growth and purpose will come to us. Perhaps, as in the passion, death and resurrection of Christ, new life will only come on the other side of the cross. Then we may hear our equivalent of what God says to the revived people of Israel: “I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I the Lord, have spoken and will act,” says the Lord.